Donatello, the Medici, and the Birth of Renaissance Genius in Florence

Donatello: Sculpting the Soul of a New Age

Long before Michelangelo’s David stood in fierce defiance in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria, there was Donatello’s David—commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici—which laid the very foundation for Renaissance art and made Michelangelo’s masterpiece possible. With chisel in hand and a bold vision in mind, Donatello reshaped the aesthetic world of 15th-century Florence, ushering in a humanist artistic revolution. More than a craftsman, he was one of the first artists to be seen as a creator—a visionary whose works reflected the shifting philosophies of his time.

Breaking with the Church: Humanism vs. Aristotelian Doctrine

The late medieval worldview, steeped in Aristotelian logic and the theology of Thomas Aquinas, posited that art served solely to glorify the divine. According to the Church’s Aristotelian perspective, art was meant to reflect idealized, hierarchical spiritual truths—there was no space for individuality or earthly emotion. The soul’s perfection, not the body’s realism, was the aim.

But in the wake of new ideas stirred by Petrarch and early humanists, Florence’s intellectual elite—Cosimo de’ Medici chief among them—began to challenge this rigid structure. Humanism emphasized the beauty of the human form, the value of earthly life, and the study of classical antiquity. Donatello’s art gave this philosophy physical form, breathing life and emotion into marble and bronze.

Cosimo de’ Medici and the Patronage of Genius

Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464), banker, de facto ruler of Florence, and cultural tastemaker, was the first of the Medici dynasty to truly cultivate a deep appreciation for the arts and to actively shape Florence into a cradle of Renaissance creativity. At a time when the Church still clung tightly to conservative artistic ideals, Cosimo recognized in Donatello a bold and innovative spirit that mirrored the emerging humanist worldview.

Beginning in the 1430s, Cosimo became one of Donatello’s most important patrons, commissioning groundbreaking works that would not only adorn the Medici Palace but also redefine the artistic identity of Florence itself. More than a financier, Cosimo served as a father figure to Donatello, offering him both material support and the creative freedom to pursue unprecedented artistic experimentation. His patronage marked a turning point in the perception of the artist—not just a skilled artisan, but an intellectual force and visionary creator.

Defying Authority: Donatello and the Bronze Bust Incident

Donatello’s reputation for artistic integrity and defiance was legendary. One famous story tells of a client who refused to pay the full price for a bronze bust, arguing that the artist hadn’t spent enough time on it to justify the cost. Donatello, incensed by the dismissal of his genius, ignored even Cosimo’s attempt to mediate. He marched to the top of the Medici Palace and hurled the bust to the ground, shattering it into a thousand pieces. His message was clear: his art was not up for negotiation.

David Reimagined: Sensual, Bold, and Revolutionary

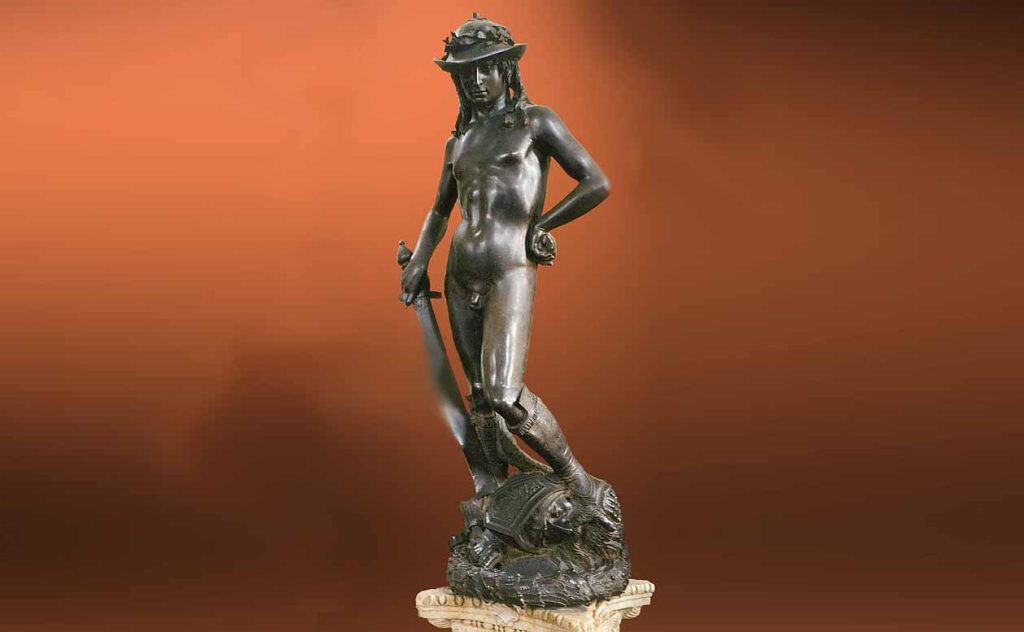

Perhaps Donatello’s most iconic and debated work is his bronze statue of David. Commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici, it stood in the courtyard of the Medici Palace—a private, powerful symbol of Florence’s triumph against tyranny. David, with his effeminate pose, soft curls, and enigmatic smile, shocked and fascinated viewers. It was the first free-standing nude bronze statue created since antiquity.

Yet, despite the sensuality and homoerotic undertones, the Florentine public embraced it. Donatello’s sexual identity—an open secret—was never a subject of scrutiny. The statue was too groundbreaking, too magnificent, to be overshadowed by anything else. It stood not only as a biblical hero, but also as a symbol of humanist liberty and intellectual courage.

Today, Donatello’s David resides in the Bargello Museum in Florence, where it continues to inspire awe and admiration.

A Legacy of Generosity and Humility

As Donatello aged, Cosimo continued to support him, gifting the artist a villa outside Florence and fine clothes. But Donatello, ever devoted to his art, wore the garments once or twice and returned to the city, choosing instead a simple life in his workshop.

There, he maintained a basket filled with money from commissions—not locked away, but available to any of his apprentices who found themselves in need. His generosity matched his genius.

Donatello’s other great works, including the haunting Penitent Magdalene in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and his Saint George for Orsanmichele, reflect the emotional depth and realism he pioneered. Each piece speaks not only to a moment in time, but to a fundamental shift in how humans see themselves and their place in the world.

Donatello’s Flame Still Burns

Donatello died in 1466, but his spirit lives on in every life-like figure, every curve of bronze, and every emotion carved into marble by the artists who followed him. More than a forerunner of the Renaissance—Donatello was its spark. Through his work and his vision, he transformed not only art, but the artist’s very role in society.

To learn more about Donatello and the Medici, I recommend Paul Strathern’s comprehensive book The Medici: Power, Money, and Ambition in the Italian Renaissance (2016), which details the rise and fall of the Medici dynasty in Florence, and Christopher Hibbert’s classic The House of the Medici: Its Rise and Fall (1974). And of course, there’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, first published in 1550—an invaluable contemporary source that offers vivid insight into Donatello’s life and the flowering of Renaissance genius.

The House of Medici: Its Rise and Fall – Christopher Hibbert

A classic! Easy to read, full of juicy anecdotes and well narrated. The perfect guide if you’re starting from scratch.

The Medici: Power, Money, and Ambition in the Italian Renaissance – Paul Strathern

Another page-turner filled with compelling stories. Strathern captures the essence of Medici power at the heart of the Renaissance.

Vasari: Lives of the Artists

These biographies of the great quattrocento artists have long been considered among the most important of contemporary sources on Italian Renaissance art. Vasari, who invented the term “Renaissance,” was the first to outline the influential theory of Renaissance art that traces a progression through Giotto, Brunelleschi, and finally the titanic figures of Michaelangelo, Da Vinci, and Raphael.